Glorious Greek Easter

Our spring, four-day celebration is by far the most significant feast we collectively observe, similar to American Thanksgiving.

These, wild saffron biscuits from Astypalaia, a southern Aegean island, are probably the most unusual of the Easter breads and cookies we traditionally bake, as they are not sweet but savory, their dough rich with fresh cheese, scented with nutmeg and allspice (more further down).

Feasting on lamb after Lent

Easter marks a massive exodus from the big cities, as people want to celebrate in the country, preferably in the open air. The holiday begins with somber days of Lent, especially during the Holy Week, when even olive oil is banished, occasionally substituted by tahini in the traditional lentil soups.

There are moving church liturgies with a strong theatrical element which peak with the solemn funeral-like mass and parade of Epitaphios on Friday evening. During Epitaphios my favorite Byzantine chant is sang by the priests and the candle-holding followers.

There is the ‘first resurrection’ on Saturday morning, but the serious feast begins after the open-air midnight resurrection mass, as the ‘holy light’ brought from Jerusalem is distributed to all candle-holding attendants, while ‘outlawed’ fireworks blast all over the country.

After the mass, magiritsa soup is traditionally eaten. In the classic recipe, all lamb’s innards –heart, liver, lungs, and so forth– go into the pot, an age-old nose to tail traditional cooking.

In my opinion the flavor of the soup comes from the boiled head and neck, and gets its distinctive irresistible taste from the scallions, the fresh dill, and avgolemono --the egg-and-lemon sauce. I often cooked chicken magiritsa in the US, as well as a wonderful vegan one with mushrooms, and my friends loved them both. Non-Greeks don’t seem to appreciate lamb’s broth and innards, and the small, 30-pound lambs we get here are not easily available in other parts of the world.

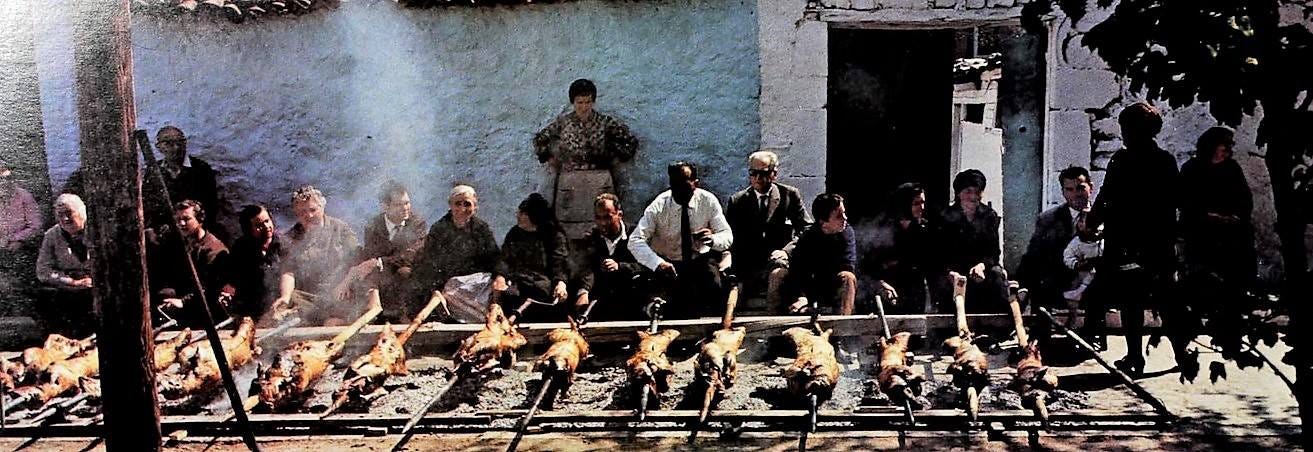

Easter Sunday’s spit-roasted baby lamb is now a fixture all over the country, although originally the tradition was mainly observed in Central Greece. In other parts, especially on the southern Aegean islands, stuffed lamb with spicy rice, sultanas, and chopped innards was wrapped in multiple layers of wet paper and left to cook slowly overnight in the receding heat of the wood-fired oven.

My mother used to dye lots of Easter eggs bright red as she liked them, and is the custom in Greece. She had a special old aluminum pot that was permanently stained from this horrible, and surely toxic red dye.

By a strange coincidence, it was my mother’s last Ukrainian companion who made me start coloring Easter eggs with onion skins, teaching me this wonderful version of what I knew as huevos haminados. She taught me how to decorate them with leaves and flowers secured on the egg with a piece of cheesecloth or torn shreds of nylon stocking. Lenio, my niece, sent me photos of the beautiful ones she created yesterday.

Kokoretsi, spit-roasted lamb offal wrapped in cowl fat and a double layer of intestines, is another exquisite Easter delicacy. Butchers sell kokoretsi ready for the grill, here on Kéa, and I suspect in other parts of the country.

I had photographed Yanni, our island’s pharmacist and roast maestro, threading the offal and wrapping the kokoretsi, but be warned that my graphic photos are not for the faint-hearted.

The yellow, Easter biscuits

Ever since I first tasted these wonderful bisquites in a bakery in Astypalaia–the butterfly-shaped, first island of the Dodecanese– more than thirty-five years ago, I’ve been addicted to their slightly peppery taste and crunchy texture.

The original, made with yeasted dough, startled me by their lightness. The large, ring-shaped cookies were fragrant with allspice, nutmeg and another aroma that I couldn’t quite make out. The baker told me it was wild saffron that the women of the island collected from the hills each November, especially to make these Easter cookies.

In the ancient texts of Athenaeus bread with saffron is described as one of the special foods served at symposia, but in modern Greece—although we produce and export excellent saffron from Kozani— we hardly ever use the precious spice in traditional dishes. I believe these cookies are probably very old, and this is the reason they contain no sugar.

The women of the island keep the tradition and bake large quantities of biscuits the weeks preceding Easter, forming them into large rings (about 5 inches across). They bake, and then dry them in the communal oven, sending some to relatives in Athens, and storing the rest in large tin boxes; they keep for a long time.

Saffron biscuits from Astypalaia

Adapted from my Foods of the Greek Islands

Somehow these cookies triggered my interest in researching island cooking. They were so unlike anything else I had ever tasted! The fat in the original yeasted dough was a creamy chlori, the ricotta-like fresh cheese produced by shepherds from the milk of the island’s semi-wild goats. I’ve experimented with various soft cheeses in the dough, since it’s impossible to find anything like Astypalaian chlori. Ordinary ricotta didn’t work. My best results were with a combination of yogurt, cream, and butter.

Makes 35-40 large and smaller biscuits

1/2 cup milk