Grape Pudding Revisited

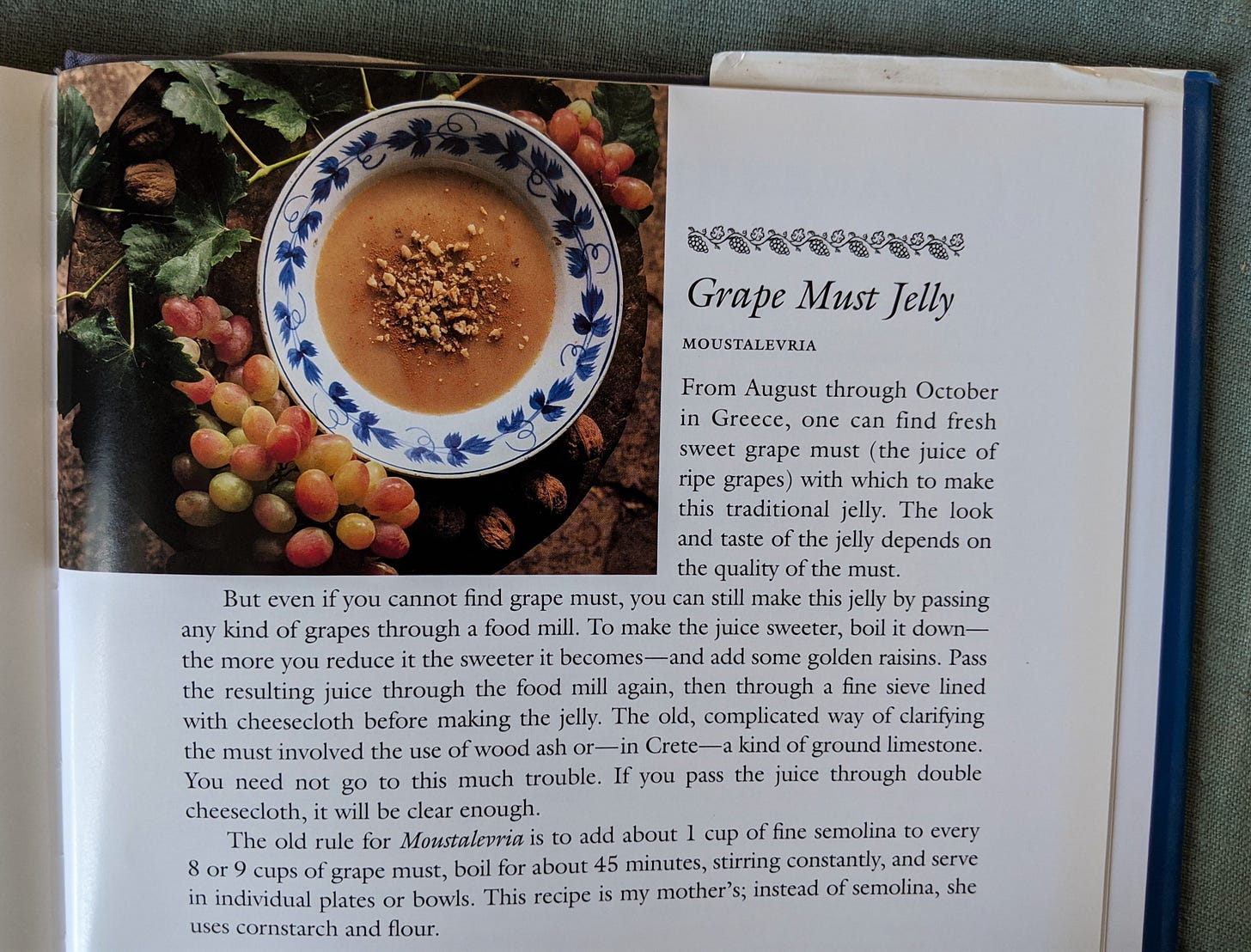

As the grapes are harvested, besides wine we also make moustalevria, the traditional grape jelly or pudding.

Most of the grapes our very old vines produce hardly manage to ripen; wasps and all kinds of insects attack them as soon as they start to blush. A couple of years back, though, we managed to harvest quite a few bunches to fill two large baskets.

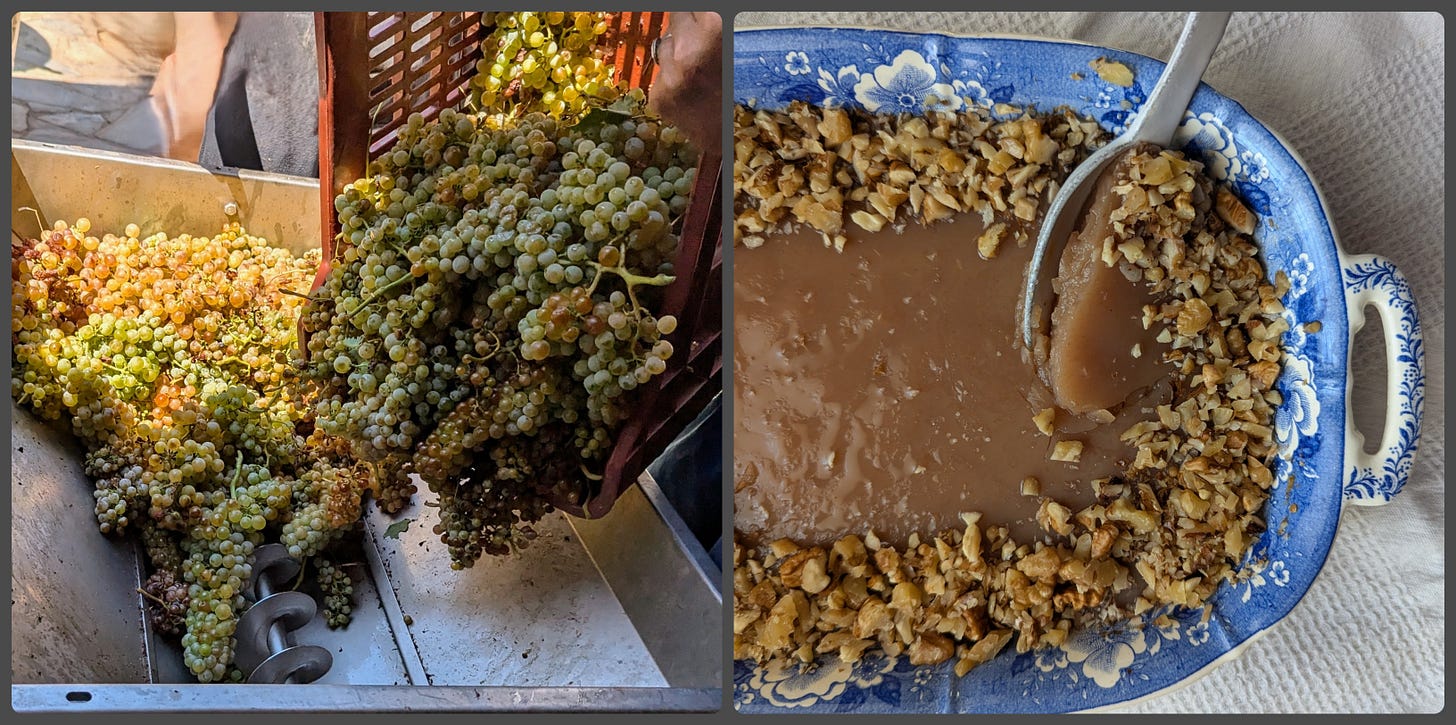

Our grapes are what the locals call krasostafyla (wine-grapes), sweet but filled with seeds and quite difficult to swallow. The two baskets of ripe grapes we gathered were too few for wine and too seedy to eat; so Costas and I decided to press them and take the juice to drink, freeze some to make granita, and certainly make moustalevria, the traditional grape must pudding our mothers used to make each year.

It was a lengthy, painstaking process starting with our grapes. But if you use the usual seedless grapes one gets this time of year, moustalevria is the easiest and most delicious summer treat, we feel.

Our vines, which give us the delicious, tender leaves for our spring dolmades, are probably a remnant of the old vineyards the little valley around our home was famous for; the dark grapes used to produce quite good wine in the old days, as I discovered researching the paper I wrote for the 2017 Oxford Symposium:

“…Kea was once famous for its red wine.” British traveler and writer James T. Bent in his 1885 book Cyclades or Life among the insular Greeks mentions that the island had extensive vineyards, many on terraced corridors in its northern slopes. Considerable amounts of wine were being produced throughout the island’s history. There was enough wine for local consumption, and until the early twentieth century some was also exported. Bent writes that Michael Psellos –the eleventh century monk, scholar, and politician– describes Kea’s wine as “sweet to the scent, and black in color,” and “much sought after in Constantinople. […] The wine of Keos is still of great repute,” […]

A vineyard at Otzias, circa 1900, from the family archives of Nikos Alexandrou.

Photographs taken at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth bear witness to serious wine-producing activity, especially in the northern part, where we live. The old abandoned, overgrown winepress I see from my office window, halfway up the terraced hill, is proof that vines must have been cultivated on the grounds around our house.”

This year our grapes were far too few for moustalevria, so last week I asked my friend Kostis Maroulis, one of the very few who produce really good wines on our island, to give me some grape must, as he was pressing the few white ones he uses to make his lovely, fruity, retsina wine.

My non-traditional moustalevria

The old recipes our grandmothers used called for a lengthy process of simmering for hours and clarifying the grape must with wood ash to make it clear, and certainly more attractive to look at —although its color was always somewhat brownish. This process takes away most its fruity, fresh flavor, but makes it sweeter and more intense.

I always skip these steps when I make my grape must pudding, which I used to call ‘jelly’ when I published the recipe in my first book Foods of Greece (1993).

But my English and American food-writer friends told me that people expect a jelly to be clear, which my moustalevria certainly isn’t, so I’d better call it ‘pudding’ they said.

I much prefer a fruity-tasting even though cloudy moustalevria, so after passing/pressing the grape juice through a double cheese-cloth, I briefly boil it, then add the cornstarch and continue cooking just until it thickens, much like I do when I make my orange ‘cream’ in the winter.

Its color depends on the grapes one uses, and if you like it red, as the one we made with our own grapes, you could add some unsweetened pomegranate juice, as I should have done with this last pudding I made from Kostis’ white grapes.

Unfortunately it has quite an unattractive color but its flavor is not too different from the previous one. Note that moustalevria is probably an acquired taste; a very subtle fruity dessert that people used to bold-tasting puddings may find tasteless…

You can use any nice grapes you like to make the juice. Be careful when you start with any of the canned grape juices available, and choose a pure juice with no additives, sugar, or preserving substances.

I fully agree with Ari Weinzweig, who wrote in his learned Top 5 newsletter about Doris Kearns Goodwin’s newest book relating the life of her husband, the late Dick Goodwin, entitled An Unfinished Love Story. “All her books—about history (primarily presidential) and leadership—are, to my taste, terrific and the new one is no exception,” writes Ari and I totally agree. I listened to the Audiobook that relates vividly the stormy political story of the sixties. The book is read by the author and includes original archival clips with JFK, Lyndon Johnson, and Bob Kennedy.

On the other hand, The Safekeep, by Yael van der Wouden, was one of the most fascinating and thought-provoking novels I have read, and I hope the young author will get the Booker prize!

“There’s organizing a fridge, and then there’s fridgescaping: the art of decorating a fridge’s interior,” I read recently in the NYT…

Our friend Maddalena Cantoni just emailed me that the same grape must pudding "In Emilia Romagna it's called sugoli or crepada."

Thanks a million, dearest friend!

Intriguing. I wonder if I will find this on a menu at a taverna or restaurant while in Greece?