Mastic: Precious and Elusive

An ancient aromatic, a vegan bread that uses it, plus a preview of the international conference that celebrates our way of eating as not only healthy for humans but also good for the planet!

The terrible fires of this summer ravaged the northern part of Chios island. Fortunately they didn’t spread to the south where the precious product of this island paradize grows —see an older post.

Chios’ mastic –the crystallized sap of the wild pistachio shrub (Pistachia lentiscus) which grows only on the southern part of this island— essential for our festive breads, was for most of the world a new and somewhat esoteric flavoring (scroll down for an unusual, delicious vegan tsoureki).

For centuries it was only exported to the Arab countries and the Middle East. Mastic was the ancient chewing gum, hence the verb ‘masticate.’

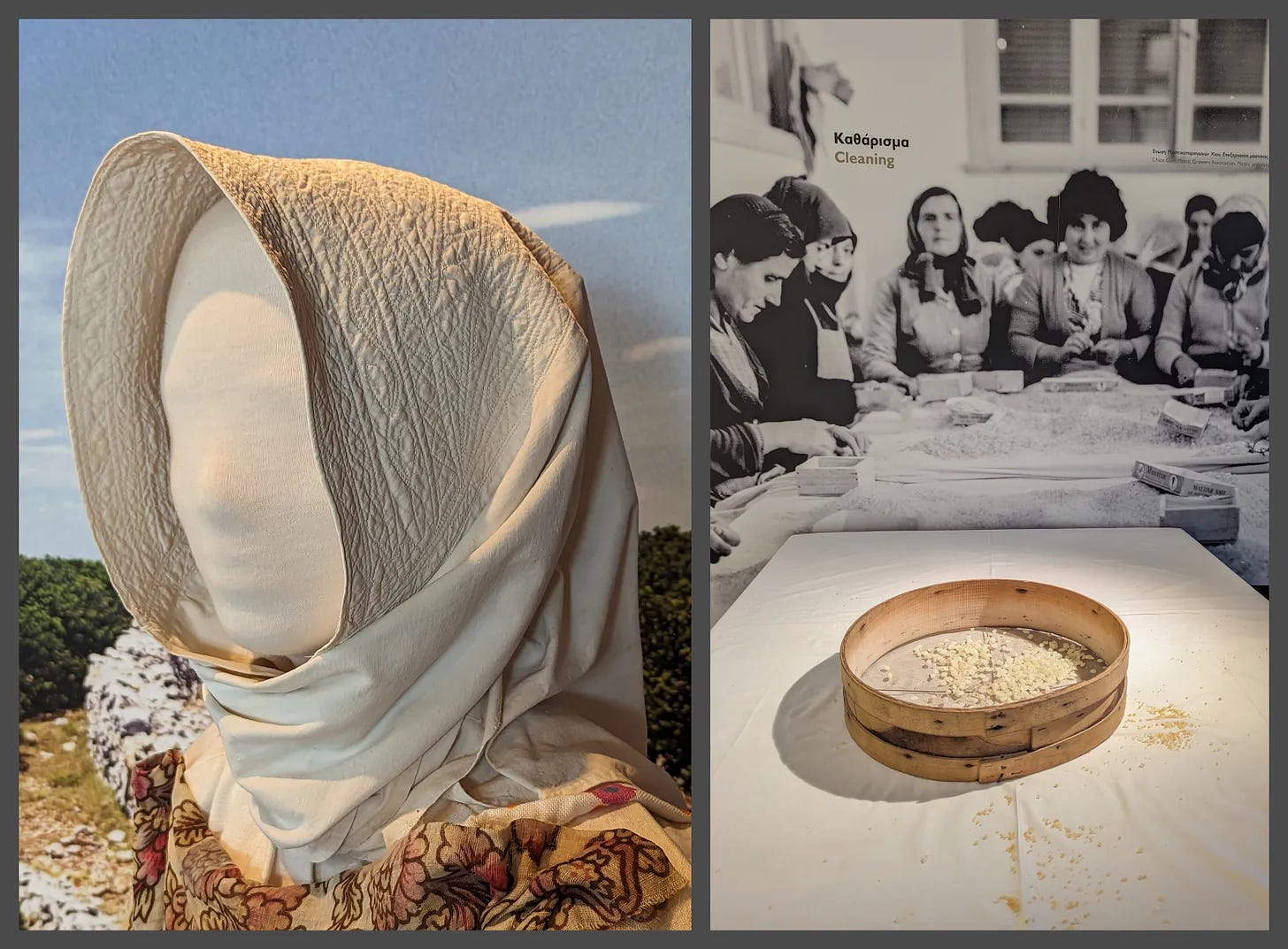

Collecting , cleaning and sorting the dried sap —the mastic tears— was a tedious work done mostly by women.

To this day mastic is still chewed in Greece to clean and sweeten the breath while the ground crystals traditionally add their elusive licorice-pine-like aroma to many traditional breads and cookies.

As kids we used to love mastic ypovrichio (submarine): a teaspoon of mastic-scented soft sugar candy served plunged in iced water, hence its name.

For years we were being bombarded by new ‘creative’ edible uses of the aromatic, like a mastic-scented olive oil which is now, fortunately, almost forgotten.

On the other hand, shampoos, face and hair masks, and other cosmetics with mastic were quite successful all over the world as they followed ancient suggestions about the crystal’s healing and healthful properties that apparently have been tested by some modern scientists, as Frank Bruni wrote in the New York Times six years ago.

Early this week scientists, doctors, chefs, and environmentalists from all over the world will be gathering in Kalamata, in southern Peloponnese, to celebrate and promote to the world our traditional everyday and festive meals as a model for healthy eating that also helps keep our planet healthy. READ MORE HERE

A vegan tsoureki

I have baked many Lenten tsourekia (plural from tsoureki), which, if you take out the eggs and butter, is essentially a kind of challah with different spices –we come to these later. But my challah-like tsoureki has not the great flavor and cake-like crumb that @BrianLevy has created.

A professional baker, author of “Good & Sweet,” a marvelous book of Naturally Sweetened cakes, breads, and other treats, Levy posted the original recipe last year; but only now I decided to try it.

Mastic crystals, ground, traditionally add their elusive licorice-pine-like aroma to many traditional breads and cookies.

I could never have imagined using creamed cashews instead of eggs. “Cashews lend themselves to being easily pureed into a fat-and protein-rich cream with a sweet, subtly nutty flavor. They even share a hint of eggs’ sulfury flavor as well as their emulsifying power,” wrote Levy in another recipe he had created.

For this one he wrote: “I’ll just say that oats, olive oil, and cashews do some amazing work here, and this recipe [vegan tsoureki] is worth trying no matter what you think of dairy and eggs.” And I couldn’t agree more!

Last fall I used the kitchen of a large resort hotel in southern Peloponnese to prepare the dishes that were photographed for the EAT-Lancet project (see above) As I was rolling grape leaves on my corner, one of the hotel’s prep cooks filled a saucepan with water, added a fair amount of cashews and placed them in the back of the stove to simmer for more than an hour.

When I asked her, she told me that they would be mashed to become the base of a vegan tzatziki. As I rely on the plethora of our traditional Lenten dishes and hardly ever try to transform into vegan dishes that are not, I had never heard or imagined that raw cashews were used to make vegan cream… Tasting this vegan tzatziki later, I found it quite good!

Enticing aroma and strong flour

The fragrant flavor of tsoureki, both the festive egg-butter one, as well as this Lenten version, relies on the sweet aroma of mastic and mahlep. Mastic is the crystalized sap of a wild pistachio shrub/tree that grows on the island of Chios.

Mahlep is the seed kernel of Prunus mahaleb (Mahaleb or St Lucie cherry). I particularly like its sweet aroma and I often use it, combined with ground coriander and anise seeds in my regular breads.

While mahlep can be ground in a spice grinder, mastic needs to be carefully crushed in a mortar, together with sugar. It tends to melt and stick to the blades of the spice grinder destroying it, so never grind mastic in the grinder.

This time of year, especially, on the shelves of Greek supermarkets we find bags of ‘tsoureki flour’ which is the strongest we can get. Stronger even than the one labelled ‘pizza flour, or 00.’ ‘Tsoureki flour’ has 26% protein, while ‘Pizza flour’ has 21%.

Lenten (Vegan) TSOUREKI

Adapted from Brian Levy.

In the original recipe the cashews and oats are mashed with cold water in a high-speed blender to get the smooth mixture. But because my blender is not the best, I used warm water to make sure no nut bits remain. I decided to skip heating the cream in a pan before adding the olive oil, since it was already quite warm. I omitted vanilla, increasing the amount of orange zest, and used more fresh orange juice.

I shaped a large braided tsoureki, which I gifted to a friend before photographing it(!) and simply twisted the log of the smaller one.

I hope Brian will not mind my shortcuts and changes…

Makes 2 braided loaves

CASHEW-OAT CREAM MIXTURE:

1 cup (115 grams) raw cashews

1 cup (100 g) rolled oats

1 1/4 cups (300 g) warm water (about 40C/100F)

3/4 tsp fine sea salt

1/3 cup (70 g) extra virgin olive oil

THE DOUGH:

1 tsp mastic (before grinding)

½ cup (100 g) sugar

The cashew-oat cream (from step 1)

4 tsp (13 g rams --2 packets) active dry yeast

Zest of 2 medium oranges

1/3 cup freshly-squeezed orange juice

5 cups (600 grams) strong bread flour

2 tsp (4 g) mahlep (mahlab)

TO FINISH: 2 Tbsp (30 g) unsweetened almond or soy milk

A handful of sliced almonds (about 30 g)

MAKE the cashew-oat cream: Blitz the cashews, oats, water, and salt in a high-power blender for a couple of minutes, until it becomes a perfectly smooth cream. Transfer to a bowl and whisk in the olive oil.

Grind the mastic: With a mortar and pestle, grind the mastic to a fine powder with 1 Tbsp of the sugar. Set aside.

Mix the dough: In a stand mixer bowl whisk together the remaining sugar, the cashew-oat cream, the yeast, zest, orange juice. (If you don’t have a stand mixer, see the Note at the bottom of the recipe.)

Heap the flour on top of the yeasted liquid, followed by the ground mastic and mahlepi. With the dough hook, mix the dough on the lowest speed just until it comes together as a mass and no scraps remain on the wall of the bowl, about 2 minutes. Stop the mixer, cover the bowl with a kitchen towel, and let rest for ten minutes. (This rest, or autolyse, stage gives the flour time to hydrate and the gluten in it time to develop.)

Knead: Remove the kitchen towel, start a 15-minute timer, and turn the mixer on to its lowest speed. The dough will be slightly stiffer than a typical brioche dough, but if it is too stiff, add a little bit of water, 1 tablespoon at a time. Pause to scrape down the sides of the bowl and to push the dough down as necessary. Once the timer goes off, stop the mixer and check the condition of the dough. If it isn’t silky-smooth, continue to knead for up to another five minutes.

First rise: Remove the dough hook and shape the dough into a smooth ball between your hands. Lightly coat the dough with olive oil. Cover the bowl (with a silicone bowl cover, a damp kitchen towel, or a large plate) and let rest in a warm spot until the dough has doubled in volume and is soft, 1 to 2 hours. At this point, you can move on to the next steps, or you can put the dough in an airtight container and refrigerate it for up to a day or two before proceeding.

Shape loaves: If you refrigerated the dough, let it come to room temperature –about 2 hours. Line a baking sheet with parchment. Lightly flour a countertop (or a large cutting board, if you don’t want to cut directly on your countertop). Use a bench scraper to divide the dough into two equal pieces, then divide each of those pieces into three (for a total of six equal pieces). Gather one dough piece into a tight ball; stretch it from the top, push in towards the center. Then stretch from the right and push in towards the center. Repeat with the bottom and left. Turn the dough ball over so it is seam-side down. Use the heel of your hand and your fingertips to squish the ball, flattening and stretching it into a thick pancake. Flip the pancake over, then, starting at the top, roll it down towards you forming a fat little log. Pinch the two ends to seal. Set the log aside on the lined parchment, seam-side down, and repeat with the remaining pieces of dough. Let the chubby logs rest, uncovered, for 15 minutes; this makes rolling them out much easier.

Using no extra flour, or the bare minimum to keep the dough from sticking to your work surface, use your fingers and upper palms to roll each rested log into a longer, thinner log, slightly tapered at the ends, about 12 inches long. Place three logs near and parallel to each other, press the three far ends together to fuse them, and braid the strands together gently; avoid pulling/tension/stretching, instead gently laying the strands atop one another. When you get to the end of the braid, press the ends together to fuse them. Tuck both ends of the braid underneath for a neat, round look. Gently transfer the braided loaf to your lined pan, placing it at a 45 degree angle so that it has room to grow. Braid the remaining three dough logs to form the second loaf.

Final rise, finish and bake: Cover the loaves with a kitchen towel or two. (To avoid direct contact with the loaves, I make a tent by setting a raised cooling rack on the pan and covering it with a few kitchen towels). Let proof until doubled in volume, 1 to 2 hours. (When you press a finger into the dough, it should bounce back only halfway, leaving an impression on the surface.)

Position a rack in the lower half of the oven with at least six inches of open space above it. Heat the oven to 180C (350°F), or 165C (about 325°F) for convection/fan oven.

With a pastry brush gently apply the milk to the entire surface of the dough, being careful to avoid significant dripping to the bottom of the loaves; you do not want a moat surrounding your tsoureki. Let the loaves rest, uncovered, for 10 to 15 minutes. (This rest allows the milk wash to dry so that another coat can be applied.) Apply the second coat of milk wash, then sprinkle the almonds over the loaves.

Bake for 35 to 45 minutes, rotating the pan 180 degrees after 20 minutes to ensure an even bake. The loaves will have risen to pillowy, glossy, deep-amber braids. If you have an instant-read thermometer, the internal temperature should be 190°F.

Transfer the loaves to a cooling rack and let cool for at least an hour before slicing.

Thank you for the kind words about my recipe, Aglaia! I’m so glad you made and liked it. And you know I’m a big fan of mastic; luckily, I still have plenty in the tin you brought me from Greece!

Utterly fascinating, Aglaia. I have included mastic in a few breads. The cashew cream is new to me. Brava!